“One hour of steady thinking over a subject (a solitary walk is as good an opportunity for the process as any other) is worth two or three hours of reading only.” - Lewis Carroll

In the present age, we read many things: e-mails, captions, comments, and text messages. Never before has the “everyday” person been inundated with so many words. One might assume that we are better readers for it. Perhaps this is true. But while we read more words than most, if not all, of our historical equivalents, rarely are we reading critically, or with any purpose at all. We wade through the slodge of notifications, group messages, and meeting agendas, leaving our word-caked wellies in the mud-room while we sit, warming ourselves up with a gently steaming cup of tea and our favorite television show at the fireside.

What if an individual wished to indulge in something more illuminating? What if they receive a copy of Ralph Waldo Emerson's Essays, or Michel de Montaigne's Essays, or George Orwell’s Essays, and decide to spend the evening conversing with one of these great writers? Might they find the prose challenging? Might they find the essay stimulating, but yet fail to articulate a day or two later the points made and lessons learned?

Or, more likely still, might this individual find themselves reading the latest Op-Ed in the San Francisco Chronicle, the LA Times, or the New York Times and have a gut reaction to agree or disagree with the author's stance, but find they cannot articulate the precise ways in which they believe the author succeeded or failed in their attempt to convince the newspaper-reading public of one thing or another?

I believe the only solution to this is to read critically, and to read often. I do not believe most schools are teaching children how to read critically. This means that many children and young adults no longer have the learned capacity to read deeply. The line between what one reads for pleasure and what one reads for (self-) education has grown thicker than Joseph Conrad's Heart of Darkness jungle, denser than James Joyce's Ulysses prose, and more insurmountable than Albert Camus' The Myth of Sisyphus hill. As a result, one’s only experience of literature might be Colleen Hoover, of poetry only Courtney Peppernell, and of philosophy whatever the latest psycho-pop self-help drivel seemingly churned out at a faster rate than we can devour them might be today.

What lies beyond? Well, one might rightly insist that there is more to learn about yourself within the pages of Hemingway's A Farewell to Arms than in Jordan Peterson's 12 More Rules for Life. That a line from John Keats or Emily Dickinson has more meaning than the complete works of Rupi Kaur. That you have more to learn about how to conduct yourself from Plato's Republic or the remaining fragments of the writings of Epictetus than from the entirely intact works of Malcolm Gladwell.1 One might rightly insist that there is an inner life worth building, and that the architecture of that inner life could be filled with Notre Dames and Big Bens and Sistine Chapels instead of pre-fabricated, mass-produced homes and repeated, forgetful storefronts.

This is not to say there's no value in Peterson, Kaur, or Gladwell. But it certainly is not an absurd proposition than one's time might be better spent with the most enduring time-tested texts of our human race than with whatever happens to be surfacing during the current zeitgeist.

And so, finally, we come to how to read these sorts of texts. And not simply to enjoy them (though that is certainly possible!), but to converse with them (and, I argue, make them all the more enjoyable in the process.)

How to Read

Often, the challenge in the task of reading is not reading the text but comprehending the text. The methods I provide here are simply my personal methods for comprehension. While I typically employ these methods for works of non-fiction, I will often utilize them for a good piece of literature, too.2

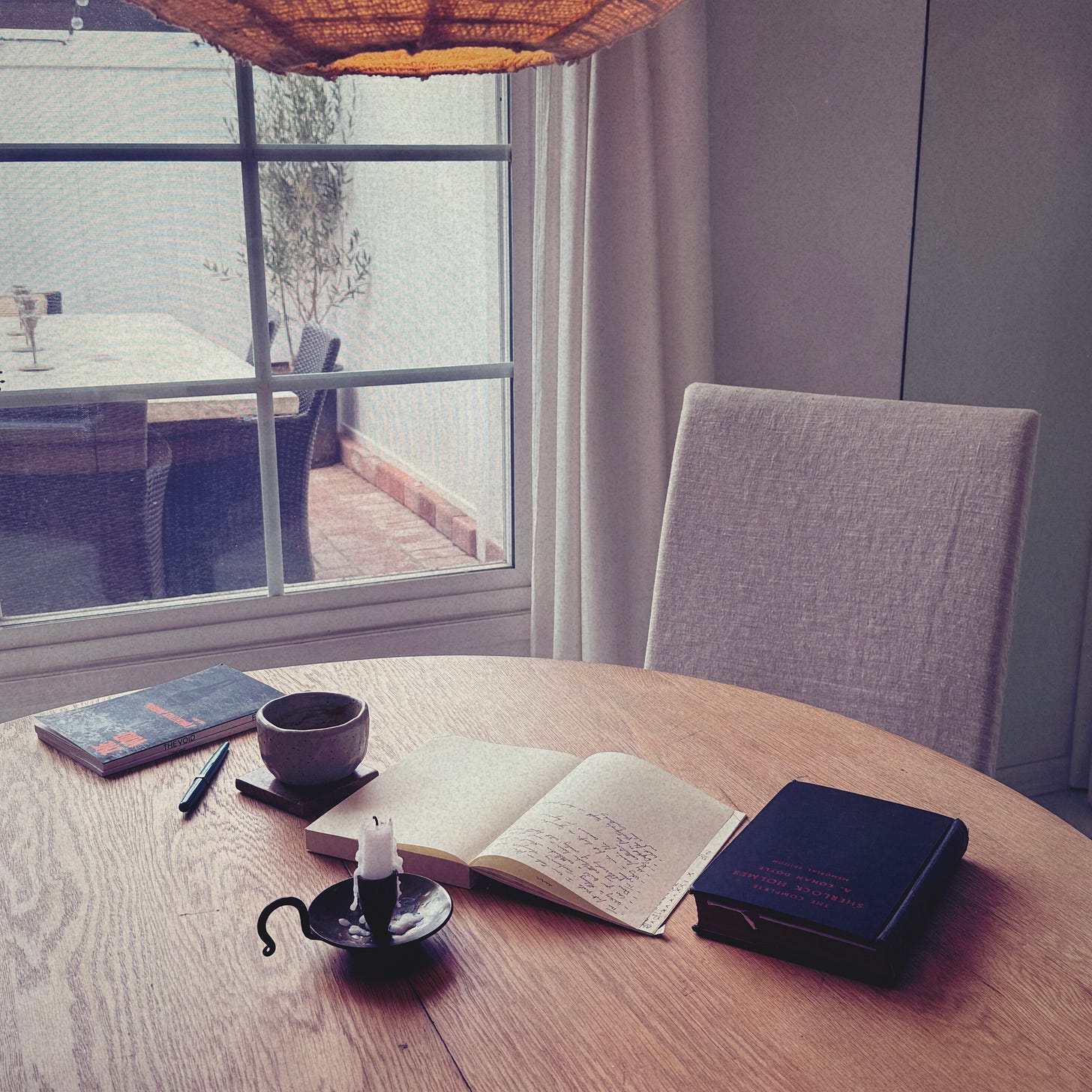

First, one must always have a pencil in hand. You may wish to use a pen, and I suppose that is your prerogative. Though a pencil seems to be the gentler choice. You may even wish to emulate the Advanced Potion Making textbook in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince and use an italicized-nib fountain pen, although I worry the ink will bleed through the page rather profusely in practice.

In many ways, we could end the lesson here: ensure you always have a pencil (or preferred writing utensil) in hand as you read. The point may be obvious, but you are to write in your text. Create marginalia. You may also keep a notebook handy to make notes of a length the margins do not allow. Alternatively, you may keep looseleaf pieces of paper inside the pages of the book for these more voluminous notes.

Doing this will enable you to begin the conversation with the text. It turns whatever you might be reading from a lecture into a conversation. And I think most people prefer conversations. You may do this in whichever way you please, but here are the general methods I seem to have procured over the last two decades of practicing this myself:

A simple * marks important passages.

/ marks indicates the beginning and end of important sentences or sections./

Large ( or ) markings across a paragraph indicate the presence of a longer important section.

_______ underlining indicates emphatically important sections.

And of course, writing notes and questions in the margins ad nauseum. If the reading is for a class, I will especially write a few words here or there to summarize that paragraph to help my later review and better reference the text in class.

Finally, though not something I practice regularly, is summarizing the contents of the page at the top of the page. (I would certainly recommend this if the text is an assigned reading for a class, say… for Core Philosophy?)

Whether you adopt these specific annotation methods or find your own preferred method of in-book notation, I guarantee that this sort of work can bring a text alive in such a way that even some of the densest philosophical tomes open up in a way you previously had not experienced.

A few other tips that you may find useful:

Leave your phone in another room and on silent.

In non-fiction, skip sections of books that are not of interest (again, unless it’s an assigned reading.)

Have a nice cup of tea or coffee with you as you read.

Do not be afraid to re-read books you've read before, or a page you do not understand. Re-reading can be most illuminating, and it is better to re-read a good book than move on to something novel but average.

Finally, if you believe you may want to make use of the text’s insights later, review your marginalia at a later time. Whatever still seems important, transfer into a notebook that you can readily access.

Many people prefer using Notion, Obsidian, or some other digital form to store these sorts of notes. I do not think it wise: let your notes exist. This way, you are more likely to return to them, to savor them, and to use them. You could even take one step further and begin your own zettelkasten, but that is a discussion for another time.

There is no time pressure to complete a reading of a good book. The culture’s focus on tracking books read and the generally technical way we approach reading now discourages slow reading and re-reading. But you can never spend too much time on a good page. There are some books I read in a matter of days, others of comparable length that I will spend a year or more with. Take your time: let your conversation with the book be the metronome establishing your reading rhythm.

All that is now left is for you to boil the kettle, pick up a book and a pencil, and have a good conversation.

A Brief Addendum

If you establish a regular rhythm of reading genuinely thought-provoking books, you may find yourself thinking about the ideas, stories, and words while you are away from your books. As Lewis Carroll suggests in the epigraph for this essay, this may happen during a solitary walk. For this wonderful, spontaneous occasion, I suggest carrying a small pocket notebook and pen/pencil to make note of the thoughts you discover. Do not use your phone for such a task. These ideas are often fleeting. As you pick up your phone to make note, you will see the text from your brother asking about dinner tonight, the email from your boss, the calendar invite from your friends, and the YouTube notification from your favorite channel. Even without notifications, you may, without thinking, check Instagram quickly and become irrecoverably distracted. The thought will be long gone.

I am aware that such arguments are often criticized for a perceived elitism. However, nothing could be further from the truth. A new book from Peterson, Gladwell or Kaur might cost $20. Plato’s works, Epictetus’ writings, and now much of Hemingway’s writings are in the public domain and freely/inexpensively available. There is no financial barrier to the type of reading I am encouraging.

Hemingway is well-known for his sparse, uncomplicated prose and so there is no additional barrier to Hemingway than with any of the contemporary books I am discussing here. There are plenty of linguistically accessible classics.

Finally, encouraging more people—especially those who might believe these books are “beyond their intellectual ability”—to read these treasured works accomplishes the exact opposite of elitism. It levels the playing field.

Now, if someone loves Rupi Kaur’s poetry, that’s wonderful. But if that same person is unwilling to take a look at John Keats or Emily Dickinson, then I merely encourage them to do so. Whether they change their opinion of Kaur after talking with Keats and Dickinson is none of my concern.

One can argue that the works of my favorite philosopher, Søren Kierkegaard, are primarily literary, and should be read first as literature before one can extrapolate any philosophical or theological meaning from them. The lines between fiction and non-fiction are not always so clear.