I Am Slowly Becoming Less Interested

An Important Announcement For This Newsletter

I am slowly becoming less interested.

Throughout my day, I often think about technology. It's role in our lives. Our obsession with it.

As a child, I loved technology. With nothing but my iPad, I read free classics, made albums of music, edited short films, championed it in schools. It was a tool of liberation for my mind.

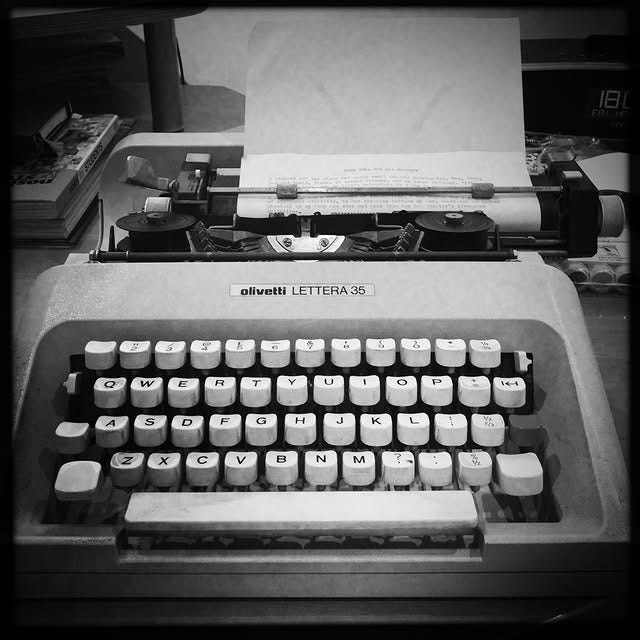

And yet when I was sixteen, I got an old typewriter. I started listening to vinyl records. I found my Dad's old SLR in the attic and starting shooting film.1

Ancient Instagram posts evidencing my age-old love of analog means of creating and enjoying art.

Fast forward fifteen years, and things look a lot different. Back then, artificially-created realistic videos were still science-fiction. Now, they're a reality. The internet is no longer a place to discover other people and their work. It's a place of saturation and artifice. But we continue to kid ourselves that it's promises are worth pursuing. Perhaps we’ll meet someone we’d never have met otherwise. Perhaps we’ll learn about something we’d never have learned otherwise.

The stark reality is that the internet has become a casino with no windows and no clocks on the wall. And yet the average American will spend more of their life looking at their phone than they will spend at school. This statistic is even more devastating when you consider how many students spend time on their phones in the classroom.2

We hallucinate benefits of this technology and convince ourselves to keep using it. But they’re not real benefits. They offer an idea of a benefit, but rarely does our experience reach those lofty heights. You, dear reader, need look no further than the platform on which you read this essay. Even Substack, filled with ex-TikTokers and Instagram influencers, along with everyday readers and writers like myself, flocked for a slower online life, has succumbed to the same tired tropes of soundbites and livestreams.

Even here, you have people using AI to generate content. You have click-baity articles and Notes. You have slop on Clips (somehow immediately.) And you have people following trends just to surf some algorithmic virality and gain more subscribers. . As someone who just wants to write and publish essays and stories and read what other people have to write, it’s fucking tiresome. And I am slowly losing interest.

I desperately don’t want people to read my words on their phone. I’d rather they didn’t read what I have to say at all.3

I am going all-in on print publication. A Reasonable Doubt will no longer feature all my essays and stories, but will serve as a field office from the Real.

Since I started The Void (my quarterly print publication) one year ago, I’ve struggled to determine whether a particular piece should only be published on this site, only be published in The Void, or both. I now have that answer:

A Reasonable Doubt will feature occasional essays, photos, and (potentially) videos solely on the idea of leaving our digital lives behind. Ways we can detach ourselves from our coded identities living on platforms we don’t control and re-experience life without all this shit that’s making other people rich and us more miserable.

So, I have decided that if I’m going to continue to have an online presence, it should only serve as a reminder for you to leave the online world behind.

For the last two years, this newsletter has grown from thirty-odd subscribers to over two-hundred. Yet I’ve felt increasingly disconnected from the people who receive my words into their inbox. I’ve slowly become less interested as the audience grew. And now, my disinterest has reached a breaking point.

From now on, if you want to read my work, you'll have to hold it in your hands.

The Void Quarterly Journal

I am the editor of The Void, a physical quarterly publication. Each edition showcases some incredibly talented friends and creatives in my community, along with my own writing. Throughout the year, The Void features poetry, fiction, and critical essays, along with film photography and other forms of artwork.

I still listen to those records. I still use that film camera. I still use that typewriter.

The same cannot be said for any of the technology I was using 11-13 years ago. I did upgrade my turntable in 2017, but that’s still going strong and should have a couple more decades in it. The rest of my stereo equipment is all approximately fifty years old and sounds absolutely amazing. The Olympus OM-1 that my father bought new in the early/mid-70s is the one I still use today. It still takes brilliant photos.

There’s a comment to make here about the demands for student loan forgiveness, but that’s part of a much, much larger conversation so I hesitate to jab phone-using students here without that context. Ultimately, there’s a question of value and that doesn’t fall entirely on the students’ shoulders: if a students’ experience felt worth $25k a semester, they likely would spend less time on their phones.

I will echo myself yet again: I would rather leave behind an analog legacy over a digital one.

I resonate with your concerns. As a pastor, the first thing I got when I came on staff was a MacBook Pro. I thought, "there are so many things I can do with this!" Now I wish they gave me a kneeler instead.

this is a bold decision, can't help but admire it! There's often a discrepancy seen even in the slow-online-living Substack community: if you preach getting off the screens and living an analog life, why constant feed posting and living off constant pipeline of paywalled essays? I get it, people need to pay bills, capitalism, etc. but after a certain number of subscriptions it feels like glorified twitter timeline with half of the posts unavailable.

I mean, in the end, Substack is just another social media, isn't it?