Contents

Introduction

Freedom is never bestowed without having to pay for it. Even in a welfare state where spectacles and toothpaste are free, freedom will still cost something. It requires risk, venture, and willingness to sacrifice.1

John Doberstein, the translator of this book of Thielicke’s essays and lectures on freedom, opens his introduction with the preceding idea. This is an excellent, though ultimately imperfect summation of the depth of thought contained in the volume, and its inclusion is likely as a result of the times.

This volume was published in 1963 to an American readership terrified of communism and convinced of its anti-Christian consequences. Communism and Christ were antithetical.

Thielicke was a German who had lived through two World Wars and was now facing the very real divide between East and West, between communism and democracy. This is where the book falls short when reading almost sixty years later. Many English-language readers simply don’t face the same imminent threats that Thielicke did. To that end, a few of the essays contained therein are more interesting biographically than theologically and did not earn much of my attention during this first reading.

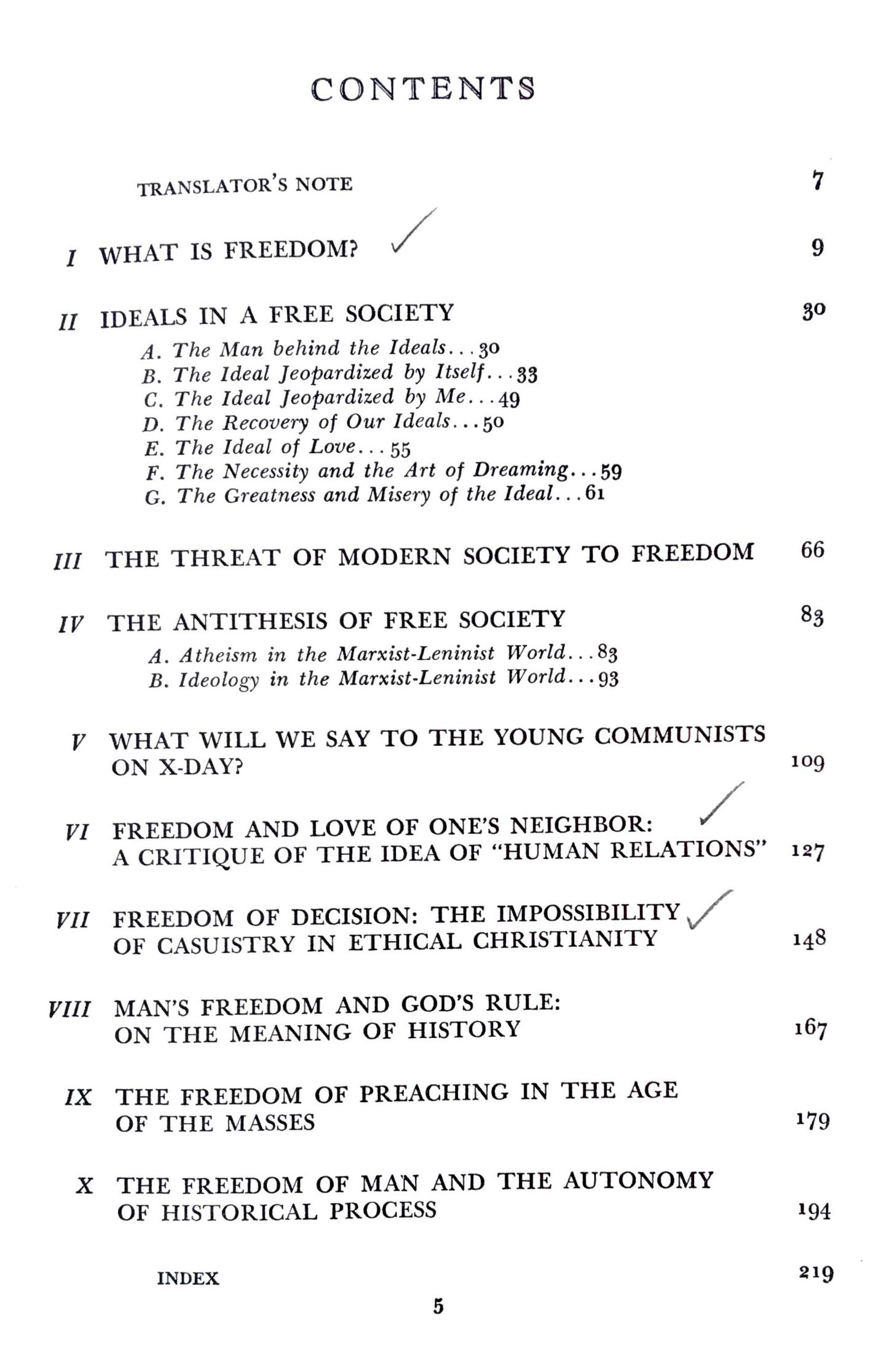

The essays contained in the volume are:2

What is Freedom?

Ideals in a Free Society

The Threat of Modern Society to Freedom

The Antithesis of Free Society

What Will We Say to the Young Communists on X-Day?

Freedom and Love of One’s Neighbor: A Critique of the Idea of “Human Relations”

Freedom of Decision: The Impossibility of Casuistry in Ethical Christianity

Man’s Freedom and God’s Rule: On the Meaning of History

The Freedom of Preaching in the Age of the Masses

The Freedom of Man and the Autonomy of Historical Process

I. Freedom

For anyone reading Luther, Kierkegaard, and Heidegger, Thielicke’s thoughts have a familiar foundation. He is also clearly in discourse with the great thinkers of his time—Sartre, in particular, is mentioned throughout as a comparative Godless freedom.

For example, one can glean from “What is Freedom?” that Sartre’s freedom, for Thielicke, is a freedom where man is freed from any nomos [law] and left to himself to create freedom. He is “obliged to usurp the freedom of God.” He imitates the Creator, and mirrors God’s freedom. But this reflection is desperate. The glass that reflects is shimmering with anxiety rather than liberation.3

Kierkegaard’s influence, even where not explicitly cited or stated, is obvious, especially in refutation of Sartre. (Sartre’s freedom and anxiety is a bastardization of Kierkegaard’s anyway.) Thielicke states that “freedom is a task set for each individual…”4 Does this not sound as though lifted directly from Kierkegaard's own text? But Thielicke offers his own spin, which is helpful even to those intimate with the melancholy Dane's work. Early on in Works of Love, Kierkegaard describes neighborly equality something like this:

The world is a stage, and life is a play. And when the curtain closes and the lights go down, both the beggar and the king go backstage and remove their costume, their cloak, and their crown. Off stage and stripped of their characters, they are one and the same: both actors.5

Thielicke runs with this idea. For him, freedom is a task that takes place on the stage of existence, with a fixed time. Even time has a telos, and end-goal, which is to achieve the task that is freedom.6

In the context of Kierkegaard, this metaphor has always intrigued me, and Thielicke’s addition only adds to its usefulness. Uncontroversially, Thielicke’s freedom can only be realized “within certain limitations.”7 This should be no surpise to the Christian thinker. This fits well within the dramatic metaphor: just as the show must go on, it must also come to an end. A play is of finite time. It has a broader meaning than the sum of its parts. The action within has a telos. Where our freedom lives within these limitations is precisely the task of the Christian individual.

This also has ethical implications. When we disagree, debate, and denounce ideas, we do so recognizing that the proponent of incongruous ideas is not defined by them as such. The proponent’s essence is not confined to the stage where we encounter them. To define them by a position they hold—or (more radically) by an action they take on stage—alone is foolish.

A reasonable conclusion from Thielicke’s ideas is that the Christian is free to love those deemed unlovable by society. Thielicke doesn’t quite make the connection within this first essay, but the nodes are already there: He states that freedom “becomes the unimpeded spontaneity of love.”8 Impeded by? What impedes love? First and foremost, myself. Let us turn (not for the last time here) to the parable of the prodigal son: when he wishes to take his inheritance and go off on his own, it is undebatable that he seeks first himself, not his neighbor. He puts himself first. Similarly when I see someone whose car has run out of fuel on the side of the road, I could easily help them get some fuel, but do I really have the time? It is I that gets in the way. Thielicke might even say—especially regarding this parable—that it is my own desire for “freedom without restraint” that impedes love.

How does this connect to being free to love the unloveable? When I am my greatest concern, I do not want to be seen offering kindness to the murderer, the fraudster, the contemporary equivalent of Christ’s tax-collector, whoever that might be. But when I am free to love spontaneously, this is no longer of any concern. I’ve “changed out my optics,” and can see beyond that person’s vocation, action, or position. In a later essay in the book, Thielicke writes that the Christian looks beyond his fellow man’s condition and sees his essence: the publicans and harlots of the New Testament are not defined as such, but rather by their essential being which transcends their actual condition. They are the children of their Father in heaven who grieves for them.9

II. Ethics

One of the most fruitful essays from this volume centers around the following thesis that Thielicke proposes:

There can be no casuistry in Protestant ethics.

By this, Thielicke means that in Protestantism (sixty years ago—things have changed) there were no “authoritative rules for making moral decisions in individual cases.”10 This is certainly true in a traditional Lutheran theological context. But it is certainly no longer the case in the broader protestant geist. American evangelicalism certainly passes down its authoritative rules for morality, along with the broader Western Church that stills sticks to the canon. But true Reformation Protestantism doesn’t offer the same clear lines, it doesn’t offer any casuistry.

God is a Homeopathic Healer

One of the most interesting elements of Thielicke’s essay here is his brief discussion of God’s homeopathic forces in the world. In Lutheran speak, this is a purely left-hand kingdom discussion. God uses “like for like” forces to curb evil. This may remind you of the “eye for an eye” so well-known from the Old Testament, but it’s deeper, more complex, more mysterious, than that. There is a positive and a negative element to this relationship. Laws exert force and restrict freedom—sometimes too much. In any event, they are a result of a broken world and exist only in that broken world. God uses those laws to curb greater evils, illegal forces. The “order of the fallen world is upheld with the means of the fallen world.”11 The world, in all its realms, lies in the "twilight between good and evil."12 This leaves us in an inbetween. There is not always a clear choice between the two, good and evil. If God uses evil to curb evil, then an "evil" is perhaps available to the human as an ethical choice in any given situation. Ethics simply measures the scope of our freedom of choices.

Here, we no longer have the “right and wrong” choices between good and evil that might seem so readily apparent from the Law of Scripture. Rather, with our freedom, we choose within a realm of ethical options that which is most readily apparent, guided by Christ, that which most loves our neighbor. Is divorce right or wrong? While it’s prohibited in the Old Testament, there is more to it with that, especially with the “new logic” of the New Testament.13 There are clearly situations where divorce is the ethical choice, especially where (Thielicke suggests) wedlock was not bound "under God" but under some other idol and/or desire.

III. Love

Briefly, and lastly, I will touch on love. It is certainly related to ethics. Love is how we are to be ethical. For the Christian, the words are almost synonymous. All ethics stem from love. Thielicke gets to the root.

Before we are commanded to love our neighbor, he says, God reveals himself to us as a lovable object. From this revealing, our love springs into action, into being a new existence which enables our freedom to “do as we will” (à la Augustine) yet nevertheless be what God means us to be.14 Reformation anthropology "insists that man is not only a subject,” but simultaneously an object of divine election and grace.15 It is not only an outward pouring of love into our neighbor that constitutes our ethical action, but it is fueled and founded on the Father who first loved us.

There is much more to be found in this volume, but the above represents a short discussion of the points most poignant to me upon my first reading. Thielicke represents something perhaps missing in contemporary theological thought: he balances the theological, philosophical, and worldly discussions and manages their interplay, yet his language is simple. In a way, he reminds one of Lewis in his masterful simplicity. While there is much in this volume that may not feel relevant today, there is just as much that is more relevant now than then, and a good amount more still that, sixty years on, produces a ring of timelessness that few writers might achieve.

Thielicke, Helmut. The Freedom of the Christian Man. Harper & Row, New York, NY. trans. John W. Doberstein. 1963, 1st. Ed. trans. note. p. 7, paraphrase.

I include this because I don’t believe the work is widely available, and this information may not be found elsewhere on the internet for those interested.

Thielicke, p. 10.

Id. at 11.

Kierkegaard, Søren. Works of Love. Perennial, New York, NY. trans. Howard & Edna Hong. 2009. (This idea can be found early in the work, though I don’t have the exact language or page # on me.)

Thielicke, p. 11.

Id. at 14.

Id. at 15.

Id. at 37. “Ideals in a Free Society”.

Id. at 148.

Id. at 151.

Id.

This phrase first used (as far as I know) by Jeff Mallinson.

Id. at 158.

Id. at 159, fn 9.