Can OpenAI Survive Ethical Interrogation?

Considering OpenAI's IP Problems From Three Common Ethical Positions

Recently, I saw a video of a live interview with Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT.1 There, the interviewer challenged Altman on the intellectual property use/theft that ChatGPT and other projects rely on in order to produce anything at all.2 This video was shared as a clip on Substack. There were many responses, all negative. Not a single Substacker came to Altman's defense.

Not that they should have, but I just thought this was really interesting. And perhaps it's representative of the type of person on Substack—someone who genuinely despises AI. But then I beg the question: where are all the other Substackers that I see criticized so often for using AI in the first place? Every day, I see people on Substack post notes claiming “if I see that your post uses AI for the title, the photo, or the essay, just know I won’t be reading it.” Personally, I have encountered very few, if any, individuals clearly using AI in their Substack essays. Perhaps they’re there, always lurking, and are too afraid to speak up on this post where the majority have made their position clear.

Anyway, the unity of hatred really stuck with me. How can we be so united that Sam Altman is—to use far less vitriolic language than my fellow Substackers—unethical when we seem to unite on seemingly simpler conflicts as often as I bake blueberry pies?3

So, I decided I should do what any good philosopher-lawyer should do, and I’m going to see if Boston was right: are Substacker’s attacks on Altman “more than a feeling”? Can I apply the three main threads of ethical theory to Sam Altman’s/OpenAI’s actions and determine on an objective ethical basis whether Altman is unethical using well-established ethical theories?

We’ll approach this from three distinct ethical angles:

Deontology

Utilitarianism

Virtue Ethics

And if you aren’t familiar with one or any of these, consider this a little “intro to philosophical ethics” along the way.

1. Deontology

1.1 What is Deontology?

Considered the child of the fascinating Immanuel Kant, deontology is a rule-based ethical theory. In other words, rational rules must be set up, and they must be universal.

This is most easily understood when contrasted with “the ends justify the means.” Here, the ends do not justify the means. It is the means that matter.

We’ll look at a couple different formulations of Kant’s categorical imperative to understand this.

1.1.1 The Universal Law Formulation

One way to understand Kant’s categorical imperative—and probably the main way—is through this idea of the “universal law.” Essentially, this means that you should “act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.”4

This demands that we consider a given action and whether, if we universalized that action, the action remains reasonably acceptable. Essentially, Kant recognized that sometimes we can justify an action in one instance, but not another. Philosophy is full of these so-called “exceptions”. For example, we know stealing is wrong, but often people will say a young boy stealing bread to feed himself and his toddler sister from a massive supermarket conglomerate is fine. Kant says no. If you universalized the principles at play there, the action falls apart. Thus, Kant says to “act as if the maxim of thy action were to become by thy will a Universal Law of Nature.”5

One example Kant provides is this: “[A man] finds himself forced by necessity to borrow money. He knows that he will not be able to repay it, but sees also that nothing will be lent to him, unless he promises stoutly to repay it in a definite time.”6 The maxim at play here is this: “When I think myself in want of money, I will borrow money and promise to repay it, although I know that I never can do so.”7 The man must ask: what would it be like if this was a universal law? “[I]t could never hold as universal law that everyone when he thinks himself in a difficulty should be able to promise whatever he pleases, with the purpose of not keeping his promise, the promise itself would become impossible … since no one would consider that anything was promised to him, but would ridicule all such statements as vain pretences.”8

So clearly, one can use Kant’s deontology to determine that in a specific instance, I should not make a promise I know I cannot keep. While I can justify doing it to myself, I cannot justify making such a promise as a universal law because then all promises would become meaningless.

1.1.2 The End In Itself Formulation

Another way to understand Kant’s categorical imperative is what I call the “end in itself” formulation, but is elsewhere also referred to as the “humanity” formulation or the “respect for persons” formulation.

This formulation requires treating other persons as inherently valuable and never a means to an end. Other persons are ends unto themselves.

Indeed, Kant writes that one must “treat humanity, whether in thine own person or in that of any other, in every case as an end withal, never as means only.”9

Again, Kant returns to the man thinking of making the lying promise to illustrate the problems with treating other persons as merely instruments: “he who is thinking of making a lying promise to others will see at once that he would be using another man merely as a mean without the latter containing at the same time the end in himself.”10 Kant takes issue with the fact that, in this scenario, the person receiving the promise cannot possibly assent to the man’s conduct because he is not aware of its dishonesty (and would never assent to it if he knew that the man was not going to keep his promise.) It therefore fails to treat that other person as a true human being, as a valuable end in and of himself, but merely a means for this man to obtain what he wants himself.

1.2 Applying Kantian Deontology to Sam Altman’s OpenAI

With these two Kantian principles in mind, let’s take a look at OpenAI and determine whether it survives Kant’s categorical imperative. This requires me to articulate Altman’s position, and I have been careful not to create a strawman but to faithfully recreate what I understand Altman’s position to be:

Altman’s position is essentially that it is permissible to scrape textual content on the internet created by others, without consent or compensation, to train large language models, if doing so results in socially beneficial outcomes or technological progress.

In the TEDtalk, Altman said that “we probably do need to figure out some sort of new model of the economics of creative output … People have been building on the creativity of others for a long time … Clearly there are things that are cut and dry like you can’t copy someone else’s work, but how much inspiration can you take? … Every time we put better technology in the hands of creators we get better creative output…” And so it’s generally results-focused.

1.2.1 Does Altman’s Maxim Survive Universalization?

Suppose that all organizations adopted this same maxim that “it is permissible to scrape textual content on the internet created by others, without consent or compensation” whenever it promises beneficial outcomes or technological advancement.

This would lead to a widespread erosion of authorship rights and intellectual property integrity. This would undermine trust, creativity, and the (inadequate) incentive structures that do exist for persons to produce new and original works.

One of the cornerstones of that incentive structure is that you get to copyright your new and original works. But copyright literally goes away once AI gets in the mix with everything we produce.

Copyright protection is appropriate only for … “original works of authorship fixed in any tangible medium of expression, now known or later developed, from which they can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly or with the aid of a machine or device.”11

Courts only require a modicum of “original creativity”:

If by some magic a man who had never known it were to compose anew Keats’s Ode on a Grecian Urn, he would be an “author” and, if he copyrighted it, others might not copy that poem, though they might of course copy Keats’s.12

But the whole question of “original creativity” goes out the window when the tool being used to create one’s own work is constantly, untraceably, infinitely using the works of hundreds, if not thousands, of others’! So while it might be justified for Altman to scrape the data in this instance, we certainly couldn’t make that a general, universalized rule.

1.2.2 Does Altman’s Maxim Survive The End in Itself?

Under this formulation, Kant clearly values the inherent dignity of each individual. Thus, Kant would value each person’s right to control how their intellectual labor and property are utilized. Scraping other people’s intellectual labor is treating that person’s work instrumentally: it has no value in and of itself, but is merely an instrument to train this far more important thing. You, as a creator, are more important in the way you feed the machine than in the valuable artwork you produce.

There is no “end benefit” that could justify, in Kant’s view, this erosion of individual autonomy, of the human “end in itself.” This instrumental use of persons’ creativity is total anathema to Kant’s view of the human as an end in itself.

According to Kant’s deontology, Altman’s practices are unethical.

1.3 Deontological Counterarguments

If a deontologist was hell-bent on arguing that Altman’s practices are ethical, what might such a pro-AI deontologist say?

Perhaps the strongest argument is that of “intention.” Kant emphasizes the importance of intention, and we can see this from the “false promise” example that he uses to illustrate his points made earlier. The whole problem with this man’s promise is that he makes the promise “with the intention not to keep it”.13 Here, Altman/OpenAI may argue that the intent of these actions is good, ethical, and proper. They may even argue that the broad, free use of others’ work to progress society is an ethical value worthy of universalization. You can make up your own mind on whether this is a persuasive counterargument to § 1.1.1, however I personally find it not so.

It also fails to overcome the “end in itself” argument in § 1.1.2: regardless of intent, OpenAI still utilizes other persons and their creative outputs as instruments rather than as ends in themselves. And there’s no getting around that one with “intent”. For Kant, good intentions can never justify instrumentalizing others.

2. Utilitarianism

Altman might have more luck with utilitarianism. While Kant is not interested in end-results or societal benefits, that’s exactly what utilitarianism looks at. And indeed, this is probably the position most pro-AI people take. Recently, while this essay was already in progress, fellow Substack/YouTube philosopher

posted a note about how he is becoming less anti-AI, and his reasoning was precisely utilitarian. After initially just posting that he was becoming “moderately pro-AI”, he later clarified that he “might still be mostly negative … but the major shift is that [he] think[s] we’re underestimating the possible benefits.”Do you see how underneath Henderson’s reasoning there appears to be some sort of scale weighing the benefits against the drawbacks? If we’re underestimating the possible benefits, then more weight should be placed on the “benefits” side of the scale and it may potentially outweigh the drawbacks. Now, Henderson did clarify that he meant “moderately more pro-AI” (emphasis mine) rather than “moderately pro-AI”, and there is a difference: I don’t think Henderson has become “pro-AI” but it does appear he’s approaching the problem of AI from a utilitarian perspective, which means that if the benefits were significant enough, he would gladly and reasonably become “pro-AI”. And I don’t think Henderson is alone here.

But let’s dig into utilitarianism proper and see if Altman and OpenAI can survive utilitarian examination.

2.1 What is Utilitarianism?

Essentially, utilitarianism holds that “actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness.”14 Happiness is roughly defined, here, as the “absence of pain.”15 John Stuart Mill’s unique contribution to utilitarianism was in this development of what precisely “happiness” or “pleasure” really is. We are not speaking merely of the pleasures that man share with the beast, but with intellectual pleasures and happiness.

Ultimately, a utilitarian investigation into the ethics of OpenAI requires an examination of the positive and negative consequences of OpenAI’s actions, and then a weighing of one against the other.

2.2 Applying Utilitarianism to Sam Altman’s OpenAI

First, let’s explore the possible positive benefits. These are the commonly presented positive benefits:

Knowledge dissemination,

Improvements to productivity and efficiency,

Social and technological innovations,

Accessibility and equity, and

Potential for compounded positive consequences as the technology improves.16

These are contrasted with the following drawbacks:

Violation of intellectual property rights

Economic loss for creators

Impact on social trust and the social contract

Plagiarism/cheating

Misinformation

Harmful/slanderous/lewd images and videos created

2.2.1 The Basic Bentham Balancing Test (Quantitative)

There are multiple ways to go about weighing the positives and negatives, and I’ll focus on two here: quantitative and qualitative. First, we’ll focus on the more rudimentary quantitative balancing test.

Here, one simply sums up the number of people experiencing happiness as a result of the action and compare that to the number of people experiencing “the reverse of happiness”/unhappiness. Whichever number is greater wins.

Under this test, OpenAI is arguably ethical. There are a vast number of users of OpenAI’s platform. In February 2025, OpenAI surpassed 400 million weekly users.17 That’s a lot of people. While it would be impossible to sum up all the people whose intellectual property has been scraped by OpenAI, the number certainly is nowhere near 400 million, especially when you consider the individual analysis needed to determine if a particular piece of information is covered by IP rights, if scraping in that instance is fair-use, and whether there is actually a harm caused to the IP owner that’s measurable.

Even when you consider the more tangible economic loss to creators such as graphic designers, copywriters, etc. who receive less jobs due to OpenAI’s ability to produce similar content, that is going to be a very small fraction of the number of users who benefit from OpenAI. And perhaps more brutally, this argument will always lose under a utilitarian examination because for every designer who doesn’t get hired, there is someone who benefits by saving money because they didn’t have to pay a designer. And that number will always be higher.

It also appears that the majority of people are not concerned (yet) about the erosion of trust and the social contract. Most people are, at best, apathetic about it because it barely affects their daily lives.

The issue of plagiarism/cheating, especially in educational environments, is real. But yet again, the numbers simply won’t be anything to sneeze at.

Similarly, the possibility of someone’s life being ruined by artificially generated images is growing, but I doubt it’s happening yet. Some celebrities may be targeted, but again, this is going to be a tiny fraction of people compared to the number of people using OpenAI every week to do whatever it is they’re using it for.

Now, we’ve covered that 400 million people are using ChatGPT every week. But are they benefitting from it? Under the qualitative test, I think we should assume so. And so under the quantitative weighing of consequences, OpenAI comes out ok. But that’s where the qualitative test comes in.

2.2.2 Mill’s More Murky Balancing Test (Qualitative)

Mill’s refinement of utilitarianism asks us not merely to tally pleasures but to weigh their depth and dignity. Intellectual and artistic creation, on his view, belongs to the realm of higher pleasures which engage the mind and elevate the spirit. Mill notes that “a being of higher faculties requires more to make him happy, is capable probably of more acute suffering, and is certainly accessible to it at more points, than one of an inferior type; but in spite of these liabilities, he can never really wish to sink into what he feels to be a lower grade of existence.”18

Undermining the incentive to create by appropriating other people’s creative output without acknowledgment or consent risks, over time, a thinning of the very cultural and intellectual fabric such technologies depend on. (This is the great irony… the more we depend on such technologies, the less “data” OpenAI will have to scrape. Thus, it’s entirely conceivable that the societal progress we so desperately cling to as a teleological justification for the current woes of this technology will slow to a grinding halt: how can we progress if no new ideas are ever injected into the ecosystem of thought?)

The problem with the qualitative test is precisely that—it’s qualitative—and so it’s not so easily judged with a clear winner. One might reasonably believe that the wide diffusion of information and educational resources with speed and efficiency still provides more pleasures than the potential harms that it also causes. Realistically, the most reasonable conclusion from a qualitative utilitarian examination is that it’s somewhat unclear now, but optimistically:

The technology will only improve, increasing both the number of people who benefit and the quality of that benefit; and

The harm will only decrease as we sort out new economic models and ways to work with human outputs that causes less social, economic, and creative harm than what we are seeing now.

With these caveats, I think Altman and OpenAI have a good shot justifying their technologies through utilitarian modes of thinking. However, one could easily use Mill to argue that OpenAI erodes creative independence. This happy “being of higher faculties” experiences a sort of long-term hedonistic degradation to become precisely what Mill thought one would never wish: to “sink into … a lower grade of existence.”

2.3 Counterarguments to Utilitarianism’s Approval of OpenAI

A utilitarian trying to show how Altman and OpenAI’s use of Intellectual Property is unethical might use the following counterarguments to what I’ve discussed above.

2.3.1 The Purported “Benefits” Are Not Benefits at All

Altman and OpenAI only succeed under utilitarianism if the positive contributions to individuals outweighs the negative contributions. So far in this analysis, we’ve assumed that the 400 million weekly users are actually benefitting from their use of OpenAI. However, this is an assumption. One could rightly argue that any and all use of AI (or at least a substantial sum of it) is actually detrimental to most users: their ability to think critically, to problem-solve, to read rigorously—all of these beneficial ways to increase human happiness for yourself and others are now outsourced. There’s a chance this is both hampering an individual’s ability to think creatively or “outside the box” and that ultimately, one experiences less pleasure in life as a result of their dependence on AI.

Therefore not only does OpenAI have a negative effect on creators, writers, and other owners of intellectual property , but it also has a negative effect on the end-users too. This argument transfers a lot of weight from the “benefits” side of the scale to the “drawbacks” side. What is left on the benefits side? Arguably, just those profiting from leveraging AI in their business models and the relatively small group of individuals using AI to genuinely make new discoveries through its computing power.

3. Virtue Ethics

Unlike other theories, which focus on law or outcomes, virtue ethics asks an ultimately much deeper question. The question is not merely what should one do, but who should one be? What kind of person or company are we becoming?

3.1 What is Virtue Ethics?

Virtue ethics originates with Aristotle and is distinct from both Kant’s deontology and Bentham’s/Mill’s utilitarianism because it focuses neither strictly on the rules nor strictly on the consequences. Rather, virtue ethics focuses on the character: what kind of person ought one be? What kind of organization ought one be? In other words:

What would a virtuous person/organization do in this circumstance?

The moral virtues commonly discussed here are:

courage,

justice,

generosity,

temperance, and

fairness.

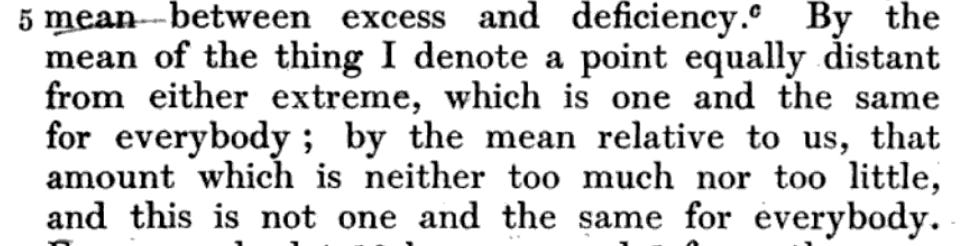

One achieves these virtues by avoiding the extremes. For example, courage sits in the “mean/average” between recklessness and cowardice. One must avoid deficiency and excess in their moral character. And this mean, depending on the context, is either objectively fixed and calculable (like a mathematical mean) or is relative to each individual: “By the mean of the thing I denote a point equally distant from either extreme, which is one and the same for everybody; by the mean relative to us, that amount which is neither too much nor too little, and this is not one and the same for everybody.”19

One’s obligation, therefore, is to determine the mean for your moral virtues and adhere to that mean as much as you can.

3.2 Applying Virtue Ethics to Sam Altman’s OpenAI

Approaching this issue from a “virtue ethics” perspective requires first identifying the relevant virtues at play here: which virtues ought a company like OpenAI be exhibiting? Which virtues should its founder/CEO exhibit? I have selected a few I believe to be relevant and shall work through them one by one.

3.2.1 Justice

First, justice clearly comes to mind. Of course, we first have to understand what justice really is. Without getting stuck in Socratic perplexity, we’ll use Aristotle’s own definition as a jumping-off point:

[W]e observe that everybody means by Justice that moral disposition which renders men apt to do just things, and which causes them to act justly and to wish what is just[.]20

Aristotle narrows this broader definition by focusing on certain aspects that he believes makes justice what it is: fairness, respect for rights, equitable distribution, and reciprocity. The two most relevant here are “fairness” and “respect for rights.”

Specifically, Aristotle discusses two sub-divisions of “Corrective” justice that apply to private transactions, which we’re dealing with here: voluntary and involuntary transactions. Voluntary transactions are “selling, buying, lending at interest, pledging, lending without interest…” etc.,21 whereas involuntary transactions are “theft, adultery, poisoning, procuring, … assassination, false witness … assault, imprisonment …” etc.22 Interestingly, the relationship between OpenAI and the creators whose content/data has been used is an involuntary one. Adding “data-scraping for LLMs” to the list of involuntary transactions does not place it in very good company.

Aristotle notes a legal maxim that has remained essentially true through to today’s American law:

it makes no difference whether a good man has defrauded a bad man or a bad one a good one … the law looks only at the degree of damage done, treating the parties as equal, and merely asking whether one has done and the other suffered injustice, whether one has inflicted and the other has sustained damage.23

Arguably, scraping others’ content and using that data to train OpenAI’s models without the consent or compensation of those creators fails to meet the demands of justice as fairness. Creators don’t receive compensation or acknowledgement, and therefore have suffered damage and injustice. That appears to be manifestly unjust.

Such actions also do not appear to show any respect for the rights that those creators hold with regards to their created content, violating that aspect of justice too.

Here, we likely have a violation of justice.

3.2.2 Respectfulness

The second virtue we will use to evaluate OpenAI is “respectfulness.” A respectful organization treats others with dignity, respects their autonomy/humanity and the inherent worth of individuals and their creative outputs. Here, OpenAI utilizes the content of others without their explicit consent or compensation. This is arguably disrespectful of that work and towards the creators themselves, devaluing their dignity and humanity. As discussed in § 1.2.2, this risks reducing humans to an instrument to some other end, which is neither respectful nor very good. This represents a considerable deficiency in this virtue.

Here, again, we likely have a violation of respectfulness.

3.2.3 Honesty/Transparency

The third virtue is something like honesty/transparency. In other words, a virtuous organization would act openly, honestly, and transparently. Especially in cases such as these where the actions of the organization not only have a significant effect not only on those who use the organization’s products, but also affect those who do not even use or agree with the organization’s work and products.

Here, OpenAI’s practices around their use of intellectual property—particularly with regards to their scraping and training of data models—have typically lacked any sort of transparency. Most, if not all, creators were unaware that their data could be and was being used until it already had been used. This is a complete deficiency in this virtue.

Is it possible for OpenAI to release the sort of information that would make it easy for anyone to see if their information had been used to train OpenAI’s model? I doubt it. I don’t think OpenAI would even know how to do that.

If the offense was correctable with some future transparency, this could be only a partial violation. But since it is not correctable, to my knowledge, this again appears to be a violation of another virtue, this time honesty/transparency.

3.2.4 Prudence

The fourth virtue we’ll look at is prudence, which means good judgment, foresight, and consideration of long-term consequences and implications of actions for society. Additionally, prudence also covers the integration of these known moral virtues into the actual practice of those virtues in one’s actions.

Here, the analysis is a little more murky. Arguably, OpenAI has been technologically prudent: it’s used publicly accessibly information to achieve significant technological advances and—arguably—societal/education advances. However, the social or legal repercussions seem to be less seriously considered: whether their actions will diminish social trust, increase creator dissatisfaction, and create regulatory backlash.

3.2.5 Generosity

The final virtue we’ll look at is generosity. Ideally, a generous entity would proactively share benefits and recognize the contributions of those whose resources it has depended on.

OpenAI does provide its product for free, only requiring subscription payment for the more advanced aspects of its technologies. This is, in a sense, generous. One imagines, too, that this is the “open” that they reference in their name, “OpenAI” (since the company’s technology is not, as the name more clearly implies, open-source…) However, there is obviously a lack of generosity towards those whose content it has used to become what it is today. The company has made no proactive efforts to compensate or explicitly recognize the contributions of those whose work has enabled OpenAI to train its models.

Thus, I would argue that the company is not generous where it counts. Furthermore, an insidious and cynical counterargument to the idea that OpenAI is at least generous towards its users would be that it is only free so that OpenAI can more easily hook its users onto its product. However, given the considerable breadth of the product available for free, I do believe many can go on using the free version without ever needing to upgrade. Any remaining counterargument involving whether it’s a good idea to make such a technology generously available would thus fall under § 3.2.4 Prudence.

3.3 Counterarguments to Virtue Ethics’ Condemnation of Altman/OpenAI

There are some, I think possibly valid, counterarguments to what I have laid out above. I will present and respond to three of them.

3.3.1 Technological and Social Benefits Demonstrate the Virtues of Generosity and Social Responsibility

OpenAI promotes education, access to information and resources, and technological progress that stands to benefit all.

Response: While true, these benefits do not nullify the violations of justice, respectfulness, and fairness towards creators. Virtue ethics demands holistic moral excellence, not selective virtue when it suits the individual/organization.

3.3.2 The Intellectual Property Used was Publicly Available and Thus Creators Implicitly Consented to Its Use

Using publicly available content is not unjust. Creators implicitly consent to public use of their work once published. Just as artists understand that their work will influence others and it may be used as an inspiration and springboard for future creators, and implicitly consent to such use in the act of making it publicly accessible, so too do online creators whose intellectual property was used for this purpose.

Response: Not only does virtue ethics explicitly emphasize explicit recognition, acknowledgement, and fairness, but more broadly, implicit consent will always be a weak argument when viewed through a virtue-ethics lens because explicit consent will always align closer to fairness and reciprocity than implicit consent.

Furthermore, while artists understand their work may be used as an inspiration, they still have rights to their created property. Furthermore, academics publish their work and make it accessible for others with the hope that it will be used and cited. But the explicit acknowledgement is integral to the entire process. Few would seek to create new and interesting ideas or research developments if, once published, another could simply copy it or use it without any acknowledgement whatsoever.

3.3.3 OpenAI’s Use of Intellectual Property Aligns with Industry Standards

OpenAI’s practices follow industry norms regarding scraping and processing internet data and so should not be penalized for using data in this manner.

Response: First, while data-scraping and similar methods have been used in the past, OpenAI’s use is distinct both in its scale and its use: never before has data been scraped on this scale, and never before has it been used to then reproduce language/images based on the scraped data in a manner that presents the result as a unique and original artifact. This means that even if OpenAI followed the existing industry norms, those norms likely should not be applied to OpenAI given the significant distinctions in how OpenAI interacts with such data.

Second, virtue ethics specifically does not value mere conformity to prevailing practices but rather evaluates the norms themselves, emphasizing excellence, fairness, and moral action. Therefore, this counterargument holds no weight from a virtue-ethics lens.

3.4 Concluding Virtue Ethics and OpenAI

Aristotelian virtue ethics emphasizes character and moral excellence across relevant virtues. In other words, an action must comprehensively express the “golden mean” between deficiency and excess across the virtues to be considered morally justified.

Here, OpenAI’s practices regarding scraping substantially fail a number of the moral virtues even if there are some arguments to be made. Therefore, from a strict Aristotelian virtue-ethics standpoint, OpenAI’s actions with respect to the use of the intellectual property of others is immoral and unjustified.

4 Concluding Thoughts: Where Does This Leave Us?

At the beginning of this essay, I discussed an interview held with Sam Altman where he was questioned about the use of others’ intellectual property. There, Altman defends OpenAI’s practices. I noted that, in response to a Substack note re-posting the relevant clip from that interview, no one came to Altman’s defense. No one agreed with Altman.

Obviously, in daily life, few of us will say “from a deontological perspective, this guy’s a real schmuck!” We simply call him a schmuck. But, based on the ethical exploration in this essay, I think we have interesting, yet unsurprising, results: three major ethical positions struggle to justify OpenAI’s intellectual property use as morally justified. Utilitarianism comes the closest, but it’s not a slam-dunk by any means.

So, where does this leave us?

AI is likely here to stay.24 And, frankly, we should recognize that it could be much worse than OpenAI. If intellectual property crimes are the main issue we have to contend with, we’re doing ok.25 However, we are still left with a choice: if the major traditions of moral philosophy agree that OpenAI’s practices regarding IP are immoral and unjustified, either (1) we rethink the foundations of our “creator economy”, recognizing the seismic shift that AI has brought to both sides of the product/user coin, or (2) we accept, in quiet complicity, the slow devaluation of human creativity.

We must ask what kind of moral world we are building as we continue to integrate AI into almost every aspect of our lives.26 If we don’t, we risk more than a mere economic loss. We risk an ethical, existential loss from which we may never recover.

OpenAI has also been legally challenged on this topic.

The New York Times sued OpenAI in December, 2023. See Imperva Threat Research. “The New York Times vs. OpenAI: A Turning Point for Web Scraping?” Imperva Blog, February 20, 2024. (“The newspaper alleges that OpenAI used its material without permission to train the AI mode. The Times is seeking “fair value” for the use of its content.” “OpenAI … argues that its mass scraping of the internet … is protected under the legal doctrine of “fair use” in the US Copyright Act.” “The Times’s lawyers state, ‘There is nothing “transformative” about using The Times’s content without payment to create products that substitute for The Times and steal audiences away from it.”

More recently, several Canadian news outlets sued OpenAI for data-scraping. See American Bar Association. “OpenAI Sued over Data Scraping in Canada.” Business Law Today, February 12, 2025. (Interestingly, in “a prior case, the Federal Court of Canada ruled that data scraping was illegal and a copyright infringement.”)

I have never baked a blueberry pie.

Kant, Immanuel. Fundamental Principles on the Metaphysics of Morals, 1785. Trans. Abbott, Thomas Kingsmill. Longsmans, Green, and Co., London, 1900. p. 46. (I recognize this does not follow the standard method for citing Kant’s works, however the public domain copy I used to reference this text did not contain the references to the Akademie volumes.)

Ibid.

Id. at 47.

Ibid.

Id. at 48.

Id. at 56.

Id. at 57.

17 U.S.C. § 102. See also, Menell, Peter; Lemley, Mark; Merges, Robert; Balganesh, Shyamkrishna. Intellectual Property in the New Technological Age 2020 Vol. II Copyrights, Trademarks and State IP Protections (Function). Kindle Edition.

Sheldon v. Metro-Goldwyn Pictures Corp., 81 F.2d 49, 54 (2d Cir. 1936).

Kant, 22.

Mill, John Stuart. Utilitarianism, 1879. The Floating Press, 2009. p. 14.

While Jeremy Bentham is considered the “founder” or first advocate for utilitarianism, I will draw exclusively from Mill here for the sake of ease: Mill takes Bentham’s utilitarianism and adds to it without altering the basics too much.

Let me know if I am missing possible benefits or drawbacks in either list.

Henderson never mentions, that I’ve seen, which possible benefits he believes we are underestimating. If I learn of what they are and they are not included in this list, I will endeavor to update it.

Kana Sato, “OpenAI’s Weekly Active Users Surpass 400 Million,” Reuters, February 20, 2025.

Mill, 17-18.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, Book II. vi. 4.

Id. at V. i. 3.

Id. at V. ii. 13.

Ibid.

Id. at V. iv. 3.

Just like in the nuclear arms race, we are left with the problematic dilemma that if we don’t develop this technology, other nations will—and to our detriment.

Of course, it is not the main issue: the ethics surrounding AI’s use in warfare, medicine, etc. is likely the largest concern but also the most hidden. These discussion should be occurring in the public eye as much as possible—it affects us all.

Clifford, Catherine. “Bill Gates on AI: Humans Won’t Be Needed for Most Jobs in the Future.” CNBC, March 26, 2025.

This is the first time I came across ethical analysis of AI like this and I loved it. Not only it got me interested in further thinking about this problem but it also got me curious what other ethics are there we can do this analysis with?! Thank you :)